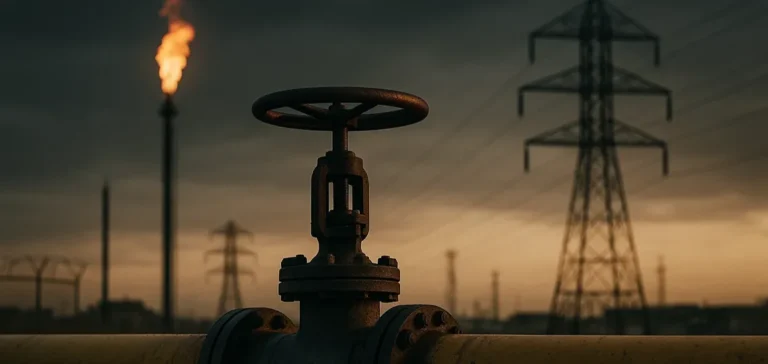

Iranian Oil Minister Mohsen Paknejad and Iraqi Electricity Minister Ziyad Ali Fadhil announced “positive results” on August 2 in their negotiations on Iraqi gas debt and future export volumes. This meeting comes as Iraq faces an exceptional heat wave and Iran has reduced its gas deliveries from 55 million cubic meters per day to just 25 million since May. Both countries claim to be approaching a settlement without revealing the financial or operational details of the agreement. This opacity reflects the complexity of an energy relationship constrained by American sanctions and the domestic challenges of both nations.

A colossal debt under the weight of sanctions

Iraqi debt to Iran for gas imports stands between $11 and $12 billion according to several diplomatic sources, although Tehran did not officially confirm any amount during this meeting. The National Iranian Gas Company (NIGC) alone claims more than $5 billion in arrears, of which $3 billion is blocked at the Trade Bank of Iraq due to international banking restrictions. Payment mechanisms remain the main obstacle, with Iraq having initiated since July 2023 a controversial barter system involving the transfer of 600,000 to 900,000 monthly tons of fuel oil to Iran. This sanctions-circumvention solution raises questions about its legality under U.S. law and could expose Baghdad to punitive measures from Washington.

The Biden administration has granted temporary 120-day waivers allowing Iraq to import Iranian gas, but the latest deadline expires on March 7, 2025. The Trump administration’s presidential memorandum NSPM-2 signals an intention not to renew these exemptions, placing Iraq in a precarious position. Contractual volumes between the two countries normally provide for 50 to 70 million cubic meters daily, adjustable according to seasonal demand, transiting through the border points of Shalamcheh and Naft Shahr. Iran sells its gas to Iraq at prices above the international market, exploiting the dependence of its neighbor which has no immediate alternatives to power its electric plants.

Iraq facing a structural energy deficit

The Iraqi electrical system operates with an installed capacity of 27 to 28 gigawatts (GW) while summer peak demand is expected to reach 45 to 55 GW in 2025. This structural deficit of 40 to 60% leaves millions of Iraqis without electricity during critical periods. The Iranian contribution, historically 10 GW representing 40% of Iraqi production, has collapsed to only 1.5 GW following recent supply reductions. Iraq paradoxically burns 17 to 18 billion cubic meters of associated gas by flaring annually, a volume equivalent to its Iranian imports, making the country the third largest waster globally after Russia and Iran.

Recent agreements with American companies including KBR, Baker Hughes and General Electric aim to capture this flared gas, while electrical interconnections with Jordan (250 MW), Turkey (300 MW) and Gulf Cooperation Council countries promise progressive diversification. The Iraqi government has announced its intention to achieve gas independence by 2028, but experts remain skeptical about the feasibility of this objective without massive investments in capture and transport infrastructure. Iraqi electrical network losses reach 40 terawatt-hours annually, four times the total production of neighborhood generators, highlighting the systemic inefficiency of the sector.

Iranian energy crisis complicates exports

Iran faces its own energy crisis with a winter gas deficit of 260 million cubic meters per day, forcing the closure of government offices in 28 provinces. The South Pars field, source of 70% of Iranian gas production with approximately 711 million cubic meters daily, suffers a pressure drop of 7 bars annually, compromising future production. Tehran has invested $20 billion in a pressure maintenance project comprising 28 platforms, but results remain uncertain. Phase 11 of South Pars, strategically close to the maritime border with Qatar, has increased its production from 15 to 18-20 million cubic meters per day.

This paradoxical situation where Iran exports gas despite its domestic shortages reflects the regime’s economic priorities, which favor export revenues estimated at $4 billion annually from Iraq. Widespread power outages in Iran and the inability to meet domestic demand create growing social tensions. The Iranian oil minister nevertheless maintains that exports to Iraq will continue in accordance with the five-year contract signed in March 2024, despite American pressure and internal criticism about prioritizing exports at the expense of national needs.

Current negotiations between Iran and Iraq illustrate the fragility of an energy relationship built on unstable geopolitical foundations. As Baghdad desperately seeks to diversify its supply sources and Tehran juggles between its domestic needs and revenue imperatives, the question remains: how long can this dysfunctional interdependence last in the face of growing international pressures and regional energy realities?