Coal currently accounts for 36.5% of the world’s electricity production. It is therefore the world’s 1st source of energy. Between 2009 and 2019, its consumption grew by 1% each year. But the future of fossil fuels is in doubt, not least because of their high carbon content.

With more and more public and private players disowning it, is its end in sight? The place of fuel in energy systems over the past ten years could provide clues as to its future.

Coal: studying the past to predict the future

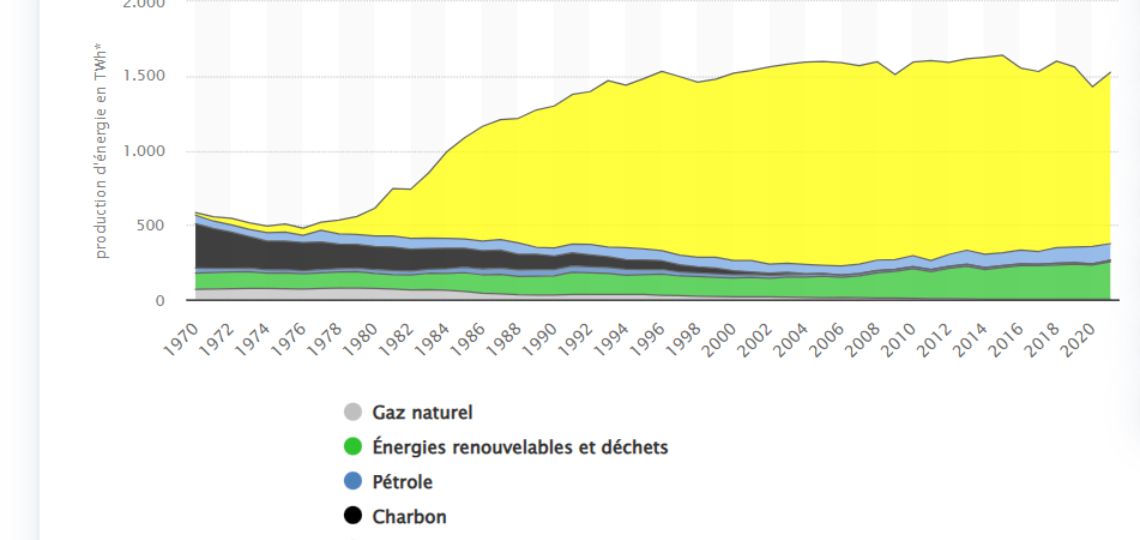

The 2000s saw a boom in the use of coal, with unprecedented growth in demand. Yet fuel demand in 2019 did not rival that of 2013. Its contribution to electricity generation fell from 40% to 36.5% over the decade. Overall, demand did not reach expected levels.

Competition from natural gas and renewable energies

On the one hand, natural gas has emerged from the American shale revolution as a competitor. Its low prices have enabled it to replace coal in the American and European energy mix. As a result, the share of fuel in the EU’s electricity mix has halved in ten years.

Wind and solar power have taken over from carbon rock, benefiting from strong political support and competitive prices. The IEA expects these energies to become the “new kings” of global electricity markets, dethroning fuel.

State climate policies

Unlike the disappointing COP15 in 2009, COP21 gave impetus to climate policies, encouraging ambitious targets. Investors are pushing companies to reduce their consumption of fossil fuels, such as BlackRock, which will no longer invest in them by 2040. Similarly, the G20 countries have affirmed their ambition to be carbon neutral by mid-century.

Over the past ten years, Western public and private players have shown a growing determination to move away from coal. Nevertheless, one region still seems to be in the spotlight: Asia.

Decline in the West, maintenance and China and growth in Asia

Today, Asian producers have replaced their American counterparts at the head of the industry. The future of the rock is now in the hands of these countries.

Sedimentary rock remains the main source of energy for the continent’s power plants. 80% of coal-fired projects, including 600 new power plants, are being carried out by a handful of Asian countries.

Asia-Pacific accounts for 75% of global consumption, up from 58% in 2009. According to Wood Mackenzie, use of the fuel is set to peak in 2027, rising to 36% of the regional energy mix by 2040. In India, for example, this resource provides two-thirds of the country’s electricity, and consumption is set to rise.

Increased Chinese control

China remains the undisputed world’s leading coal producer. According to theInternational Energy Agency (IEA), fuel will continue to account for 30% of electricity generation in 2050. Beijing sees this resource as a social stabilizer, particularly in the stricken northeastern provinces.

The rock also serves as diplomatic leverage for China, which has just imposed an embargo on Australian coal. It is seeking to reduce its energy imports so that it can then export. This strategy contributes to China’s economic sustainability, as well as that of coal.

Energy essential to Asia’s energy needs

Electricity demand in Southeast Asia has grown by 6% a year over the past two decades. For the time being, coal is the only resource capable of responding to exponential economic growth and consumption. Neither renewable energies nor gas are viable for producing electricity in sufficient quantities.

Despite its high CO2 emissions, this fuel makes up for the intermittent nature of renewable energies. What’s more, the latter are less competitive due to the region’s unfavorable topography. In island states like Indonesia, coal has the advantage of being easily transportable from one island to another.

Reinventing the world’s 1st power source

However, a new type of coal – green coal – could provide an alternative to its carbon-rich counterpart. Unlike coal, which takes millions of years to form, its production is relatively flexible. The organic waste it contains also helps avoid the deforestation needed to produce charcoal.

Coal and its green alternative, both derived from organic matter, have similar calorific values. But burning alternative fuels emits fewer greenhouse gases than burning conventional coal. Some companies, like EDF, have already tried to convert a thermal power plant to green coal.

Rethinking power plants

To meet the challenges of climate change, coal-fired power plants will have to be modernized or converted. The introduction of desulfurization and denitrification systems could be a solution. Alternatively, more cost-effective and less polluting “supercritical” power plants could be developed.

Co-combustion plants also appear to be efficient, such as EDF’s Cordemais plant in Loire-Atlantique. They use the green alternative mentioned above.

Thermal power plants can also be converted into energy storage centers. Siemens Gamesa, for example, has launched ETES (Electric Thermal Energy Storage) technology, which uses “Carnot batteries”. This involves absorbing excess electricity, transforming it into heat, which is then stored and extracted to power generators and turbines.

These innovations could offer a second life for thermal power plants, while retaining a place for fossil fuels.

A place for coal in the energy transition?

Global coal production over the last ten years therefore reflects the future of this resource. While fuel as humanity has known it since the Industrial Revolution is waning in the West, it’s still on the rise in Asia. Nevertheless, its decline is not yet sealed, as emerging technologies could bring coal back into fashion. In particular, those relating to carbon capture and storage (CCUS).