Between 2010 and 2024, global battery demand increased more than forty-fold, driven mainly by the growth of electric vehicles. At the same time, average battery prices dropped by over 90%. In 2024, the global battery market was worth around $130bn, exceeding the combined net oil imports of Germany, France and Italy. This shift also transformed the structure of demand: electric vehicle batteries now account for approximately 75%, far ahead of portable electronics, which have fallen to 5%.

A dominance rooted in two main chemistries

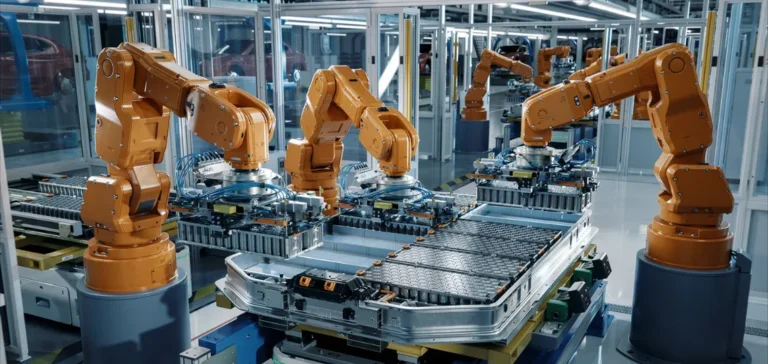

The electric vehicle battery market is currently dominated by two types of chemistries: lithium iron phosphate (LFP) and lithium nickel manganese cobalt oxide (NMC), each accounting for about half of the market. LFP is rapidly growing due to its lower cost and longer lifespan, particularly in stationary storage systems. However, supply chains for both chemistries remain highly concentrated in Asia, especially China, raising concerns around supply security and resilience.

Despite these risks, innovation in alternative technologies has not yet broken this dominance. Advances in sodium-ion batteries, for example, have led to early commercial applications in China since 2023, but this technology remains cost-effective only in the context of high lithium prices or with significant improvements in energy density.

Promising innovations constrained by industrialisation

Solid-state batteries, which offer potential for longer range and better safety, have attracted major investments, but production remains limited. BYD plans to launch commercially in 2027, with mass production expected by 2030. Toyota and Samsung have announced similar timelines. However, these technologies are still in the prototype phase, and integrating them into large-scale vehicles remains uncertain.

Lithium-sulphur batteries are being explored for specialised applications, particularly in the defence sector. They offer higher energy density per kilogram but require more space for the same energy capacity, limiting their appeal for conventional electric vehicles.

Technological lock-in persists at the production level

The vast majority of battery production capacity planned by 2030 remains focused on lithium-ion technology, with 95% of projects aligned with this chemistry. In comparison, solid-state batteries represent only about 1% of planned capacity, and sodium-ion about 4%. Moreover, 80% of these alternative projects are located in China, limiting their global reach.

Industrial data highlights the lead taken by established manufacturers. In 2024, Chinese firm CATL invested over $2.5bn in research and development, employing more than 20,000 researchers. Meanwhile, fundraising for battery start-ups fell from more than $7bn in 2021 to around $2bn in 2024, making it harder for new players to enter the market.

Targeted opportunities in high-value segments

Even if emerging technologies are expected to capture only a limited share of the market by 2030, the sector’s rapid growth provides room for manoeuvre. Premium segments, where customers seek high performance and range, may allow new entrants to position themselves by capitalising on higher margins.

The ability to scale up quickly, manage supply chains and build a skilled workforce will remain decisive. Actors capable of transferring these capabilities to new chemistries will have a greater chance of competing with lithium-ion leaders. For now, current dominance depends as much on technology as on the industrial ecosystem built around it.