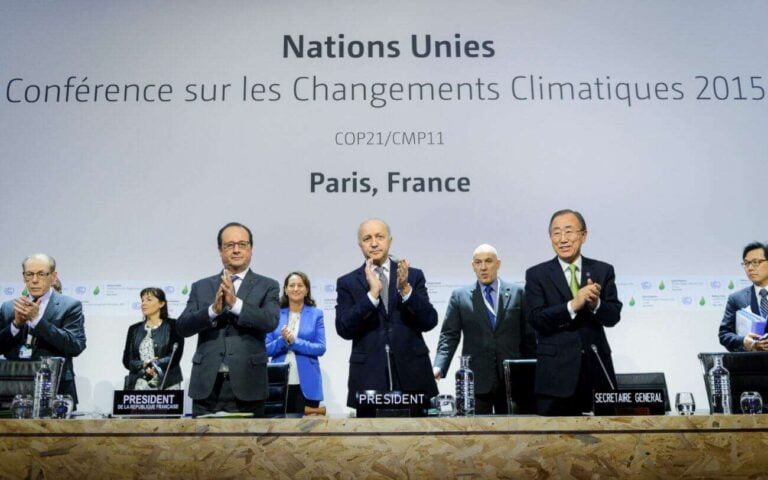

The Paris Agreement is back in the news five years after it was signed at COP 21.

Withdrawn under Donald Trump, the United States is set to rejoin the agreement under the incoming Biden administration.

The appointment of John Kerry as delegate for climate affairs symbolizes this break after 4 years of climate skepticism in Washington.

Above all, the reintegration of the USA will enable the agreement to cover almost 90% of global C02 emissions.

As a result, the stated objective of limiting temperature rises to 2 degrees once again seems attainable.

For many scientists, a rise of 1.5 degrees will already have disastrous consequences for biodiversity.

Similarly, the reinstatement of the United States could facilitate the release of the 100 billion dollars a year promised at the COP.

That’s why it’s important to look at the current state of the agreement before Biden officially takes office.

Considerable progress since the Paris Agreement

Ratified by 183 countries, the Paris Agreement has been in force since November 4, 2016, and represents the vast majority of polluting countries.

In this respect, it represents a significant diplomatic success in an era of weakening multilateralism and rising nationalism.

Above all, for the first time, the agreement provides for equitable burden-sharing between countries.

Each signatory state submits a national contribution, the NDC, in which it sets out its economic decarbonization plan.

To date, many countries have announced ambitious targets to be reached within the next 30 to 40 years.

These include Europe, which accounts for 10% of CO2 emissions and is aiming for carbon neutrality by 2050.

Japan and South Korea, as well as New York and California, have also announced similar targets.

Finally, China, the world’s biggest CO2 emitter, is aiming for carbon neutrality by 2060.

These stated ambitions are accompanied by a genuine industrial drive to decarbonize our economies.

Private companies such as Amazon and Microsoft are committed to the ecological transition.

Jeff Bezos has even launched a $2 billion investment fund to finance low-carbon technologies.

Similarly, financial giants such as BlackRock have announced that they will no longer support polluting activities.

From a technical point of view, low-carbon technologies are increasingly competitive with fossil fuels.

According to Bloomberg, lithium-ion batteries will reach cost parity with gasoline engines by 2024.

This year alone, renewables also account for 90% of the world’s installed electrical capacity.

Progress still insufficient to meet targets

Unfortunately, the progress seen in recent years still seems insufficient to meet the commitments made in the Paris Agreement.

In a special report published in 2018, the IPCC estimated a temperature rise of 3 degrees by 2100.

However, this report took into account the national contributions of States to the 2015 agreement.

Even though it was published before the announcements on carbon neutrality, the report shows the inadequacy of the measures taken.

The problem is that it’s difficult to decarbonize energy mixes today.

Firstly, energy systems are characterized by strong inertia and the existence of “path dependencies”.

For example, consumption habits are an obstacle to the replacement of combustion-powered vehicles by electric ones.

Similarly, installing energy-efficient infrastructure is often prohibitively expensive for households and the private sector.

Secondly, the energy system is not yet capable of integrating 100% of intermittent renewable energies.

Without storage solutions, they force power grids to rely on fossil fuels for reserve capacity.

Last but not least, many industrial sectors, such as steel and air transport, will be very difficult to decarbonize.

In the air transport sector, neither batteries nor hydrogen are currently alternatives to jet fuel.

The problem of financing

The issue of financing is central to the implementation of the Paris Agreement.

The signatory states have pledged to create a “Green Fund” with an annual endowment of 100 billion euros.

This fund is intended to finance projects to mitigate emissions and adapt to climate change in poor countries.

The aim is to help these countries cope with the risks of rising sea levels or drought.

However, since its inception, the fund has never succeeded in achieving its objectives.

Indeed, from the outset, countries have differed on the question of funding sources.

For many countries, the 100 billion target included all climate-related funds.

In other words, public development aid can be included in the Green Fund.

For poor countries, this is unacceptable, as donors tend to overestimate the climate component of aid.

What’s more, a large proportion of this aid is not a subsidy, and must therefore be repaid.

For example, instead of the promised 100 billion a year, the Green Fund actually has only 8 billion.

By way of illustration, this represents just over 2% of the French budget.

For years, however, governance issues have been blocking the reforms needed to revitalize the Fund.

In particular, the consensus rule on the Board of Directors acts as a powerful blocking factor.

It should be noted that the Board is made up of 12 representatives from the North and 12 from the South.

A stalemate destined to persist if nothing is done about governance.

Indeed, in terms of emissions and financing, the Paris Agreement is still far from having delivered on its promises.

Joe Biden’s victory could nonetheless accelerate reforms, particularly in the governance of the Green Fund.