The British government is restructuring its nuclear regulatory framework following the conclusions of the Nuclear Regulatory Taskforce, which identified the United Kingdom as the most expensive country in the world to build a nuclear plant. This reform, described as a “radical reset” by its authors, aims to lower investment costs, accelerate planning processes, and enable large-scale industrial deployment around European Pressurised Reactors (EPR) and Small Modular Reactors (SMR).

The Office for Nuclear Regulation (ONR) and several environmental agencies could be merged into a single commission, designed as a centralised regulatory one-stop shop. This change seeks to eliminate redundancies across safety, environmental impact, and planning authorisation procedures. The total regulatory cost, including design, construction, operation, and decommissioning, is estimated at several tens of billions of pounds over the project lifecycle.

More flexible planning and expanded nuclear land eligibility

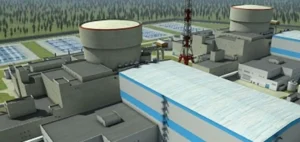

The updated National Policy Statement for Nuclear Power Generation ends the closed list of eight pre-authorised sites adopted in 2011. The new rules now include SMR and AMR (Advanced Modular Reactors) technologies, allowing their deployment on industrial areas, disused sites, and zones close to end-use demand, such as data centres or hydrogen hubs.

The Wylfa site in Wales has been selected to host the first Rolls-Royce SMR park, marking the beginning of a broader site selection process. Great British Energy – Nuclear (GBE-N) has been mandated to propose, by autumn 2026, a list of new sites able to accommodate at least one gigawatt-class reactor, including in Scotland, despite opposition from the Scottish government.

Targeted reduction in environmental constraints

The Fingleton report proposes a reassessment of the cost-benefit balance of certain environmental standards, notably those related to marine wildlife protection. At Hinkley Point C, the additional costs linked to fish protection systems are estimated at several hundred million pounds. One option under consideration is to replace some physical requirements with environmental offset mechanisms funded by a dedicated nature fund.

The possibility of building reactors near urban areas, currently restricted by zoning constraints, is also being examined. This regulatory shift aims to bring production closer to end-use sites, particularly for high electricity-demand industries, and to reduce infrastructure investment in transmission.

Institutional centralisation and project prioritisation

The Advanced Nuclear Framework adopted under the Spending Review formalises a division of roles: GBE-N screens and evaluates projects, the National Wealth Fund (NWF) considers equity investments, and the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ) designs support mechanisms, including the Regulated Asset Base (RAB) model and Contracts for Difference (CfD).

GBE-N becomes the sole entry point for any nuclear project seeking state support. This centralisation aims to shorten evaluation timelines, harmonise assessment criteria, and increase investment pipeline visibility for financial stakeholders.

Operational impacts and political tensions

The implementation of regulatory reforms raises several issues. In the short term, the transition between the old and new frameworks could slow the processing of certain projects, creating an imbalance in how developers are treated. The establishment of the new regulatory commission, announced within three months, entails a profound reorganisation of sector governance.

Politically, including potential Scottish sites in calls for expressions of interest, despite devolved planning authority, could trigger legal disputes. Additionally, proposed adjustments to environmental standards have been opposed by more than 25 civil society organisations, who fear a weakening of safety and transparency safeguards.

Towards lower nuclear capital costs

The government estimates that regulatory simplification could significantly reduce the levelised cost of electricity for future projects. By comparison, Hinkley Point C, built under the CfD scheme, operates on a guaranteed price of £92.50/MWh indexed to inflation, while Sizewell C, partially financed through the RAB model, aims for a cost 20 to 25% lower due to earlier remuneration and a reduced risk premium.

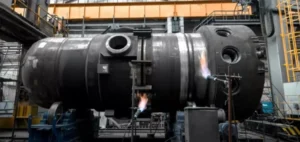

A more predictable regulatory framework could also improve the bankability of SMR projects, whose unit cost remains high at this stage. Rolls-Royce targets a cost range of £1.8 to £2bn per 470 MWe unit, contingent on securing sufficient domestic orders to justify construction of the module factory planned for 2026.