The maintenance programme for France’s nuclear fleet, estimated at over €100bn from 2014 to 2035, has become a structural pillar for EDF. This funding covers extensive works required to extend the lifespan of reactors to fifty or sixty years. The amount, as assessed by the Court of Auditors, remains more competitive than the full replacement with new EPR2 reactors, whose first six units are projected to cost between €67bn and €75bn, in addition to nearly €100bn in grid upgrades for Enedis. This decision structurally anchors France’s energy strategy until 2060.

A financial equation dominated by the state shareholder

The extension is based on a Levelized Cost of Electricity (LCOE) of around €51/MWh, provided production targets of 350–370 TWh by 2026–2027 and 400 TWh by 2030 are achieved. The grand carénage is primarily financed through cash flows from the existing fleet, supplemented by debt and public contributions. Meanwhile, the EPR2 programme benefits from a state-backed loan covering at least 50% of its cost, along with a Contract for Difference (CfD) mechanism capped at around €100/MWh. The State’s involvement in financing, pricing, and industrial planning heightens concerns of a conflict of interest, as it simultaneously controls strategic, financial, and regulatory levers.

The Court of Auditors notes that annual maintenance spending has surpassed €6bn, an increase of 28% compared to 2006–2014. EDF must manage this burden while pursuing a total investment plan of approximately €460bn by 2040, covering networks, EPR2 units, and renewables. Despite record earnings exceeding €10bn per year, EDF’s debt stands above €50bn, making the performance of its current fleet essential.

Governance under heightened regulatory oversight

EDF, fully renationalised in 2023, operates 57 reactors across 18 sites. Fleet availability has dropped to 74% from 2014 to 2024, compared to 80% in the previous decade. Reactor extensions require approval through ten-year inspections by the Nuclear Safety Authority (ASN), which has imposed stricter post-Fukushima standards. Market operations fall under the supervision of the Energy Regulatory Commission (CRE) and the Financial Markets Authority (AMF), responsible for transparency and compliance.

With the ARENH mechanism being phased out, long-term contracts with electro-intensive industrial clients will follow a new framework. The French Energy Code allows administrative suspension or termination of contracts in case of abuse, increasing regulatory pressure on EDF to offer competitive prices while securing capital expenditures. The State’s simultaneous role as regulator, shareholder, and financier amplifies scrutiny over potential conflicts of interest, particularly in the design of the new pricing framework.

Market risks and industrial tensions

The report confirms that extending the existing fleet remains the lowest-cost option compared to new nuclear capacity or renewables with backup. A prolonged and more available fleet could stabilise wholesale prices by anchoring them to a lower French nuclear floor, contrasting with Germany and the UK, where reliance on gas remains high. Conversely, shortfalls in availability or cost overruns could bring the grand carénage’s actual cost closer to that of EPR2s, increasing reliance on imports.

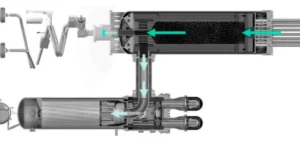

The supply chain is facing growing strain from overlapping maintenance and EPR2 construction schedules. Engineering, heavy components, and logistics capacities are increasingly tight, risking bottlenecks and rising costs. Industrial and financial partners such as Framatome, Enedis, equipment suppliers, and bond investors are directly exposed to capital allocation choices influenced by political priorities, which fuels concerns about conflicts between industrial imperatives and public decision-making.

Legal framework, transparency and international exposure

The European Commission continues to scrutinise public support schemes, including subsidised loans and CfDs, under state aid rules. However, nuclear energy now qualifies under the EU’s green taxonomy subject to certain criteria, supporting France’s legal position. EDF has been sanctioned by the AMF for financial disclosure issues and by the CNIL over data protection, prompting increased demands for transparency on project risks and costs.

EDF is not listed on the EU or OFAC financial sanctions registers, allowing it to operate trading and international projects without direct compliance constraints. Nonetheless, this status requires vigilance in selecting counterparties to mitigate exposure to secondary sanctions. These considerations highlight EDF’s dual responsibility to maintain legal compliance while demonstrating that state-driven decisions do not unduly favour the public owner’s interests.

Governance architecture likely to attract criticism

The Court of Auditors aims to formalise cost comparisons to reinforce the political narrative around extending the existing fleet ahead of the 2026 investment decision on further EPR2 units. Publishing a €100bn+ figure while affirming its competitiveness provides the government with a clear argument. It also supports the design of long-term pricing and strengthens the State’s case for defending combined public support to legacy and new nuclear before the European Commission.

France’s nuclear path could become a reference for EU-wide debates. Delivery on cost control, availability, and pricing stability will shape the credibility of this model as other countries re-examine their supply strategies.