The European carbon market has been in a state of flux since the EU tightened its commitments to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Carbon prices have thus reached record highs since the beginning of the year. This could be bad for competitiveness. Speculation on this market could seriously disrupt production costs.

Carbon market to accelerate the reduction of GHG emissions

The carbon market was set up to accelerate the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions. Under this CO2 emissions trading scheme, greenhouse gas emissions are capped. The authorities allocate quotas corresponding to these ceilings. Organizations buy and sell these quotas according to their needs.

At European Union level, while the targets set are indeed aimed at reducing emissions, they have also contributed to a surge in allowance prices (+50% since January 2021). Investment funds are also fuelling this spectacular rise.

Understanding the carbon market

The carbon market works in such a way that a public organization (the European Union, the UN, the State) decrees, for industrial installations and power plants, a level of carbon emissions not to be exceeded. To do this, they allocate them emission quotas corresponding to this ceiling (1 quota = 1 tonne of CO2). At the end of the year, manufacturers have to prove that they have respected the ceiling.

However, as the ceiling is lower than what the installations currently emit, there are two options. If an organization exceeds its cap (i.e. emits more CO2 than authorized), it must purchase the missing quotas. Conversely, companies and industries that have successfully reduced their emissions can resell the allowances they have not used.

A system born of the fight against the destruction of the ozone layer

The carbon market is therefore the place where greenhouse gas emission rights are traded. In the wake of the

Montreal Protocol

on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer (1987) that carbon credit trading systems came into being.

Visit

Kyoto Protocol

which came into force in 2005, has largely favored the quota trading system. As a public policy tool, it aims to encourage industries to reduce their emissions by cutting energy consumption or investing in low-carbon technologies. It’s the “polluter pays” principle.

Offset by financing projects to reduce other CO2 emissions

It is also possible to offset emissions. It works on the principle of the universality of CO2 (carbon). According to this principle, CO2 diffuses throughout the atmosphere, wherever it is emitted.

The aim of carbon offsetting is to counterbalance unavoidable carbon emissions by financing projects aimed at reducing other CO2 emissions. This process is put in place when an organization cannot reduce its own greenhouse gas emissions to achieve or approach carbon neutrality.

Although it mainly concerns CO2 emissions, it also applies to other greenhouse gases, such as nitrous oxide and methane.

One way among many to put a price on carbon

there are other ways of pricing carbon as a negative externality alongside the market.

Carbon taxes, for example, tax manufacturers in proportion to the emissions generated by the production of goods and services. This tax, passed on to the end consumer, increases the price of the good or service. This has the effect of favoring the cheapest product, and therefore the one that generates the least pollution.

European carbon market: the EU Emissions Trading Scheme

Quotas are traded either over-the-counter between manufacturers, or on specific markets. Within the European Union (EU) and the European Economic Area, the market is called the European Union Emissions Trading Scheme (EU ETS).

The EU created the SEQE in 2005 as part of its ratification of the Kyoto Protocol. Now entering its fourth and final phase (2021-2030), it covers 45% of the EU’s greenhouse gas emissions and applies to over 12,000 industrial and energy installations.

Achieving the EU’s 55% CO2 emissions reduction target by 2030

In the early stages of the EU ETS, each country set up its own plan for distributing the millions of quotas among its manufacturers. The first ceilings were set by total quota volumes.

The 2013-2020 period saw the emergence of the European ceiling as we know it today. It is being steadily reduced to lower the volume available (-1.74% per year). However, this reduction of 38 million allowances will accelerate over the period 2021-2030 to reach the target of a 55% reduction in CO2 emissions by 2030 compared with 1990.

Beginning of the end of free quotas

While quotas were distributed free of charge during the first phases of the ETS, this is now less and less the case. In fact, some sectors no longer receive free quotas (power plants, for example). Part of the quotas are auctioned.

Other sectors, meanwhile, are facing what is known as “carbon leakage”. The relocation of industries in order to avoid the carbon tax. There is therefore a risk to the competitiveness of some of them.

Tonne of CO2 equivalent at €45

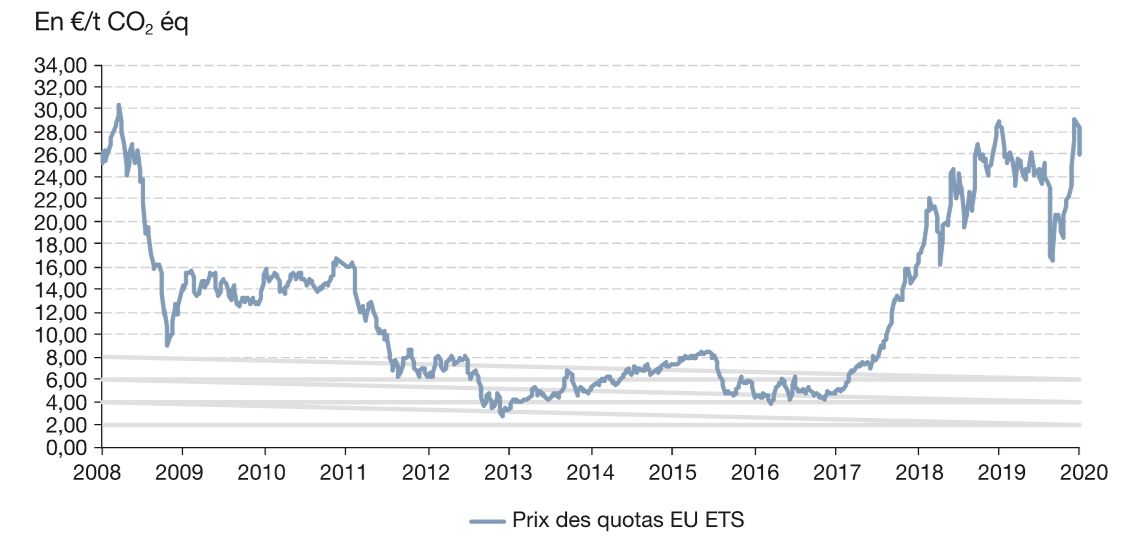

In 2008, the price of quotas was €30/tonne. However, the economic crisis of 2008-2010, combined with policies to support renewable energies, led to a surplus of allowances. This market imbalance has caused prices to fall by more than 50%, or even 90% at times.

It wasn’t until 2017 that the European Commission initiated reforms aimed at driving up prices (to around €25-30/tonne of CO2). By 2021, the CO2 equivalent ton has risen to €45.

900 million allowances to be auctioned for 2019-2020

For the period, 2019-2020, 900 million have been put up for auction. By applying tiers to quota volumes, the EU has tried to curb surplus quotas over the long term. To this end, it has created the Market Stability Reserve (January 2019).

Finally, in the last phase of the SEQE, the EU has reformed the market’s operating rules. As a result, the pace of emissions cap reductions is accelerating. It will therefore increase from 38 to 48 million tonnes/year from 2021.

Risks of carbon leakage and destabilization of competition

The Stability Reserve and the intensification of climate targets reinforce the credibility of the European carbon market as an effective means of combating climate change. Indeed, these measures mechanically drive up prices. Nevertheless, the anticipation of supply reduction risks making CO2 prices disconnected from industrial reality. We’re talking about €100 per tonne in 2030.

Since the beginning of the year, around a hundred non-industrial investors have entered the market. These new players hope to speculate on prices. The latter consider that emissions allowances are financial products, making the market highly volatile.

Speculation could seriously disrupt production costs

These soaring prices are likely to drive up production costs. This will undermine the competitiveness of our industries and could lead to carbon leakage. As proof, on the European market, CO2 has reached the €50/tonne mark.

The solution could therefore lie in a new reform of the ETS. Nicolas de Warren, President of the Union des Industries Utilisateurs d’Energie (Union of Energy-Using Industries), which groups together major French industrial companies, said:

“These costs reduce manufacturers’ capacity to invest in decarbonizing their manufacturing processes. He adds that the volume of allowances available to non-industrial investors should be limited.

Other players believe that the deployment of the Border Carbon Adjustment Mechanism (BCAM) is a necessity. This border carbon tax, scheduled for 2023, is intended to charge importers a price equivalent to that paid by players on the European carbon market.