On the world map of green hydrogen in 2050, North Africa is the world’s leading exporting region, and Europe the leading importing zone. A study by Deloitte reshuffles the global deck when it comes to energy and, potentially, the industry of the future.

Green Hydrogen and the Prospect of a Market in 2050

The emergence of green hydrogen, linked to that of renewable energies, “will reshape the global energy and resources landscape as early as 2030, and could ultimately constitute a market worth $1,400 billion a year”, asserts this study, published at the height of summer.

In May, the World Hydrogen Council collaborated with McKinsey. This partnership has identified more than a thousand green hydrogen projects, requiring $320 billion for commissioning before 2030. The Council was created in Davos in 2018 by the sector’s leading industrialists.

By 2050, according to Deloitte, the main exporters of green hydrogen should be “North Africa ($110 billion per year), North America ($63 billion), Australia ($39 billion) and the Middle East ($20 billion)”.

Decarbonization and Diversification of Green Hydrogen Applications

To reduce greenhouse gas emissions, the growing need for green hydrogen is decarbonizing industries. These include petrochemicals, steel and cement. Heavy transport such as aviation and shipping are also thirsty for hydrogen to replace fossil fuels, as they cannot rely on electric batteries like cars. The production of green hydrogen from the sun or wind can also be used to “inclusively” develop industry in emerging countries, the report hopes.

Challenges and prospects for Green Hydrogen in the face of Grey Production

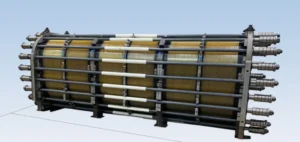

For example, it could help develop the steel industry in southern countries. But at present, 99% of the world’s industrial hydrogen is “grey”, produced from methane gas on petrochemical sites, an operation that releases large quantities of greenhouse gases like CO2 into the atmosphere, and contributes to global warming. And less than 1% of hydrogen can be described as “green”, derived from the electrolysis of water, which separates oxygen and hydrogen atoms using an electric current. The green hydrogen of the future will come from the electrolysis of water using wind, solar or hydraulic power. Some current experiments are even betting on production directly at sea, alongside wind turbines and desalinated seawater.

North Africa: Assets and Opportunities in the Green Hydrogen Landscape

This is where North Africa has a card to play, according to Sébastien Douguet. The head of economic consulting at Deloitte also co-authored the study. This is based in particular on modelling data from the International Energy Agency (IEA).

“Several North African countries, such as Morocco and Egypt, are taking up the hydrogen issue, and hydrogen strategies are being announced there, only a few years behind the European Union and the United States”, notes the researcher.

“Morocco has a very strong wind energy potential that is often underestimated, and a great solar potential, and Egypt has the means to become the main exporter of hydrogen to Europe in 2050 thanks to the already existing natural gas pipelines” that would be reallocated to hydrogen, he explains, interviewed by AFP.

Challenges of the Green Economy and Public Policy Coordination

“In our study, we assume a halt to investment in 2040” in the capture and storage of CO2 emitted during the production of hydrogen from methane gas, the current strategy of the oil-producing countries of the Gulf, but also of the United States, Norway and Canada, adds Mr. Douguet.

The hydrogen produced in this way is not labeled green, but “blue”. Several countries are betting on the transport by ship of intermediate carriers such as green kerosene, methanol or ammonia. The hydrogen would then be extracted on arrival at the port. According to Mr. Douguet, this strategy has already been launched in Japan and Korea, which import ammonia, and in Australia, which produces ammonia.

“This green economy can become profitable for end customers, provided that public support for the establishment of infrastructure is long-term and public policies are coordinated”, warns the author of the study, however.