The National Oil Corporation (NOC) is set to award around 20 onshore and offshore oil blocks as part of its first exploration round since 2008. Thirty-seven companies have been prequalified, including several international majors. The move comes as Libya’s oil output stands at 1.4 million barrels per day (Mb/d), with a government target of reaching 1.6 Mb/d by 2026. At the same time, gas exports to Italy have fallen to their lowest level in over a decade, leaving the Greenstream pipeline underutilised.

Two governments, one recognised exporter

The country remains divided between the UN-backed Government of National Unity (GNU) in Tripoli and a rival executive in Benghazi supported by Khalifa Haftar, who controls key eastern oil fields and ports. Despite this, NOC retains exclusive international recognition as Libya’s sole legal oil exporter.

In May 2025, eastern authorities threatened to declare force majeure on several terminals, highlighting the vulnerability of Libya’s crude flows to political manoeuvring. The UN Security Council renewed its sanctions regime in 2025, keeping Libya’s oil exports under close international scrutiny.

A legal framework under compliance pressure

Libya’s upstream oil sector is classified as “strategic industry”, requiring foreign companies to operate through joint ventures regulated by NOC. New production sharing contracts (PSCs) are expected to include enhanced anti-corruption and transparency clauses after recent fuel-smuggling scandals led to an estimated $6.7bn in losses in 2024 alone.

International operators must comply with sanctions frameworks from the United Nations, European Union and United States. The US Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) has already targeted oil-smuggling networks operating in Libya, raising the bar for corporate due diligence.

Unused capacity versus saturated global supply

Libya holds proven reserves of approximately 48 billion barrels. With much of its infrastructure already in place, the country could raise output to 2 Mb/d with an estimated $3–4bn in capital expenditure. However, the International Energy Agency (IEA) projects rising non-OPEC+ supply, potentially dampening the market impact of any additional Libyan output.

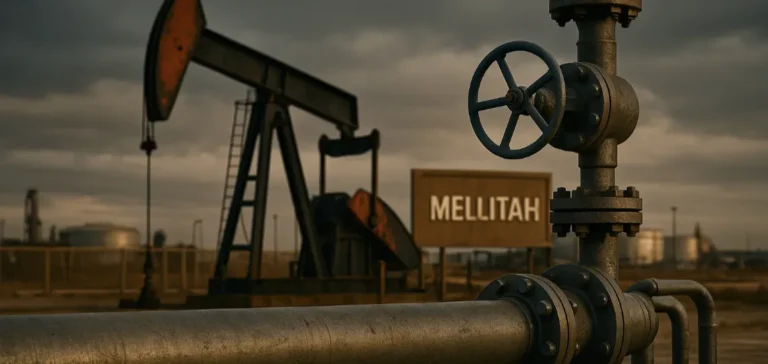

Gas flows to Italy through Greenstream have hit a 13-year low. Eni, which controls about 80% of Libya’s gas production, is structurally positioned to rapidly monetise new discoveries. Shallow offshore blocks near Mellitah are considered particularly valuable.

Diverse bidders in a fragmented landscape

Among the 37 prequalified companies are BP, TotalEnergies, Chevron, Shell, ExxonMobil and national oil companies such as Sonatrach, QatarEnergy and CNODC. The broad bidder base could reduce political dependency and increase competition. Meanwhile, entities such as Arkenu, linked to Saddam Haftar, have exported at least 7.6 million barrels outside NOC’s official channels.

The blocks on offer are primarily located in the Sirte Basin, onshore desert zones and shallow offshore areas with existing terminal access. While this lowers infrastructure costs, it increases exposure to port blockades.

Governance and image risks for operators

Firms will need to include contractual safeguards against production halts. Terminal blockades have previously cut national output to near zero. Libyan institutions have launched internal audits, but their enforcement remains uncertain.

Fuel-smuggling operations involving political and security actors from both sides of the conflict continue to raise red flags. Operators will need to prove their hydrocarbons do not pass through illicit channels, or risk reputational damage and legal exposure.

Commercial and geopolitical implications

Short-term market reaction to the licensing round announcement has been minimal, given typical development timelines of 5–7 years. If successful, the round could add 0.3–0.5 Mb/d by 2030, reinforcing Libya’s role as a marginal supplier of medium-sour crude in the Mediterranean.

On the gas side, higher volumes to Italy would marginally reduce Rome’s LNG reliance, though Libya remains a minor supplier at EU level. For Libya, signature bonuses and local content requirements provide near-term foreign exchange inflows and job creation.

International oil majors see competitive development costs and infrastructure tie-back opportunities. However, they must manage exposure to unstable governance, ESG risks and potential sanctions.