In Montlhéry, south of Paris, the Eodev Eneria CAT plant’s production lines are firing on all cylinders.

Hydrogen: The Silent Revolution of Ecological Festivals

The hydrogen generators that emerge promise to produce electricity without emitting CO2 or fine particles. It’s enough to make you forget about those noisy oil-fired generators, which are as bad for the climate as they are for your lungs. From the foothills of the Auvergne volcanoes to the Bay of Saint-Brieuc, eco-responsible summer festivities are turning to hydrogen instead of diesel to produce huge amounts of watts and decibels in remote locations, far from the power grid.

“90% of the event industry relies on generators – there are thousands of them everywhere – but they pollute enormously, emitting both CO2 and carbon monoxide,” admits Jérome Bourdel, Sales Director of GCK Energy, a manufacturer and rental company of traditional mobile electrical equipment, and also an Eodev customer.

He lists his latest contracts for green hydrogen generators: “In June, for the Nuées ardentes scientific festival in a protected natural area at the foot of the Puy-de-Dôme, in Clermont-Ferrand for the Europavox music festival or on the roadside, during a stage of the Tour de France”.

One tonne of CO2 per day

In the Côtes d’Armor town of Hillion, in the Bay of Saint-Brieuc, the “Folies en Baie” festival on August 6 and 7 was equipped with hydrogen-powered generators. Belfort’s “Eurockéennes” at the beginning of July. In the summer of 2022, the Futur 2 festival in Hamburg, Germany, boasted that it would be the “world’s first festival” to be powered by wind-generated hydrogen. The construction industry is also a major customer. Construction sites are looking to green their operations by moving away from conventional, polluting generators.

“A 100-horsepower diesel generator can emit up to a ton of CO2 in a single day to produce 1 MW of energy – the equivalent of a passenger flying from Paris to New York and back – not to mention the noise and atmospheric pollutants such as nitrogen oxides and NOX,” points out Thibault Tallien, Marketing Director of EODev.

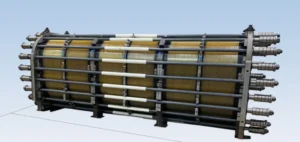

The company has been producing hydrogen generators for three years on a production line at the Eneria CAT plant in Montlhery. It is based on scientific demonstrations carried out on board the Energy Explorer laboratory ship, which has been propelled around the world autonomously by solar, wind and hydrogen energy since 2017. The core element of the generators coming out of this plant is a Toyota fuel cell, produced in Belgium. Through an electro-chemical reaction between hydrogen protons and electrons, it generates electricity.

Other equipment – frames, radiators, electrical panels, wiring – comes from French SMEs. Connected to racks of compressed hydrogen gas cylinders certified “green” by their producer (i.e. from wind, solar or even hydro-electric power), the generators look like large, silent white refrigerators, and emit only water vapour.

“We produce 150 a year, exported all over the world, and can go up to 600,” says Mr. Tallien.

Four times more expensive

A potentially gigantic market. Worldwide, sales of gensets passed the $20 billion mark in 2022, and “should double by 2030 to between 4 and 6 million units a year”, estimates Mr. Tallien.

70% run on diesel, 26% on gas, and 4% are hybrids. The main drawback of green generators is their cost. Each unit costs “four times as much” as a diesel generator, says Tallien.

“But it has a better yield”. At GCK Energy, Jérome Bourdel admits that he “struggled for the first two years” to “prove the value of the concept” to his customers. “But once they’ve tested it, they adopt it,” he says.

The downside is that 1 kWh of electricity from hydrogen costs 2 euros, compared with just 30 centimes for electricity from the grid, and 1 to 1.20 euros from a conventional oil-fired generator.

So, for the craze to last, “the real challenge is to bring down the cost of green hydrogen”, he stresses.