In Colombia’s 2022 presidential campaign, Gustavo Petro is defending an ideology that transcends the traditional left-right divide. The latter offers the Colombian people a choice between a “politics of life”, focused on environmental protection, and a “politics of death”, anchored in dependence on fossil fuels. The reason: beyond Petro’s desire to make Colombia a leader in the global energy transition, his country is highly vulnerable to climate change. Firstly, Colombia is home to almost 10% of the world’s known species, earning it the title of “megadiverse” country. In addition, the country is increasingly affected by floods, landslides and water shortages. During his campaign, Petro also emphasized the need to protect the Amazon, a statement enthusiastically welcomed by environmentalists. His plan to halt oil exploration, meanwhile, has business circles worried.

On May 29, 2022, he led the first round of the presidential election with over 40% of the vote, followed by businessman Rodolfo Hernández. The absence of an absolute majority for Petro leads to a second round in June. Despite predictions of a disputed second round, Petro won with over 50% of the vote to Hernández’s 47%. His victory marked the historic first election of a left-wing president in Colombia, and his running mate Francia Márquez became the country’s first black female vice-president.

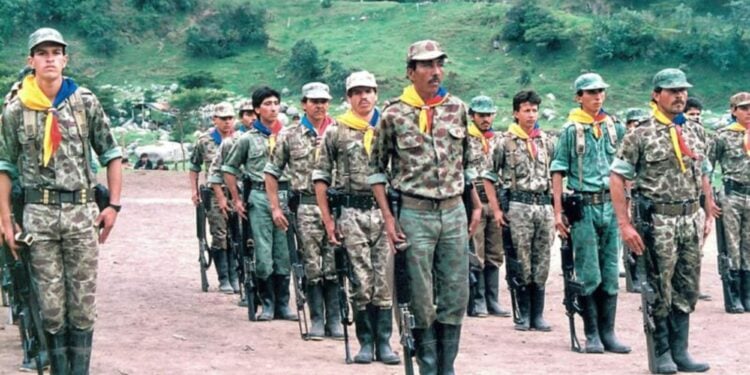

Gustavo Petro has been an active member of the M19 since the age of 17. A Colombian urban guerrilla movement, while maintaining the importance of class struggle, it rejects the ideas of Bolshevism, the dictatorship of the proletariat and the single party. Instead, the M19 pursues the goal of revolutionary social democracy. In short, he sought to transform the structures of his country’s traditional liberal democracy. Like many other Latin American countries, Colombia is marked by a highly oligarchic system. Petro was an M19 activist until the movement’s demobilization in 1990, as part of a peace agreement with the Colombian government.

In 1991, Gustavo Petro entered the Colombian House of Representatives under the colors of Alianza Democrática M-19. His path, however, took an abrupt turn in 1994 when life-threatening threats forced him to leave his homeland. He found refuge in Brussels, where he worked as a diplomatic attaché until 1996. On his return to Colombia, he resumed his seat in the House of Representatives in 1998.

His political commitment in 2006 led him to the Colombian Senate. There, he distinguished himself by becoming one of President Álvaro Uribe’s most fervent critics. Gustavo Petro raises serious accusations implicating politicians, members of the security forces and President Uribe’s brother in drug trafficking and collusion with “death squad” groups. These stances won him growing popular support, which he channeled into a presidential bid in 2010. Although he only finished fourth, this election marked the start of a remarkable rise.

In 2012, Petro began a term as mayor of Bogotá. It launches programs such as subsidized water and transport rates for the most vulnerable citizens. These programs are helping to reduce crime and poverty in the capital. However, his plan to reform the garbage collection system turned into a disaster. This led to piles of garbage in the streets, and to Petro’s dismissal by the Attorney General’s office in 2013. However, an appeal to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights enabled him to regain his position the following year. This setback, far from marginalizing him, strengthens his image on the Colombian left. In 2018, he ran again for the presidency and succeeded in a run-off against Iván Duque. The latter won with 54% of the vote. But in 2022, Petro is running for president for the third time. We already know the rest of the story.

Since his election to the presidency, many of Gustavo Petro’s campaign promises in the energy sector have come to fruition. From this point of view, the most striking measure of the current Petro presidency is undoubtedly the announcement, in January 2024, that his government would not sign any new hydrocarbon exploration contracts. An ambitious measure, given Colombia’s dependence on fossil fuels, particularly oil.

Hydrocarbon taxes, dividends and royalties account for 15% of Colombian government revenue. Exports of oil and coal account for over half of the country’s total exports (55%). But as Petro announced at COP28 in Dubai: “Today, we are witnessing a huge confrontation between fossil capital and human life, and we have to choose sides. We choose the side of life”.

Another notable measure of Petro’s presidency is the absolute ban on hydraulic fracturing, or fracking. By banning fracking, Colombia is depriving itself of the equivalent of 3,000,000 million barrels currently present on its territory. As well as being a way out of the oil business, this measure also has environmental implications. Hydraulic fracturing generally involves injecting 80 to 300 tonnes of toxic substances into the ground. At the end of the operation, almost 80% of these toxic substances remain in the ground, sometimes reaching the water table.

Conservation of the Amazon rainforest is also at the heart of Gustavo Petro’s ecological policy. In August 2023, the Colombian President, together with Lula and the leaders of the six other Amazon countries (Bolivia, Ecuador, Guyana, Peru, Suriname and Venezuela), re-launched the Amazon Cooperation Treaty Organization. While the eight governments agree on the need for “innovative financing” programs to safeguard the Amazon (such as external debt swaps), Petro’s Colombia and Brazil take it a step further: both countries commit to achieving “zero deforestation” by 2030. To achieve this goal, the Colombian president wants to discourage industries such as palm oil and sugar cane, which are harmful to forest conservation. These are used in particular to produce soft drinks, which are very popular in South America. So, to combat these powerful industries, Petro introduced a system of very high taxes on the consumption of these drinks.

Reactions and opposition to environmental and climate policies

In Colombia, the energy transition is definitely gathering pace under the Petro presidency. However, we can imagine that in a country heavily dependent on hydrocarbons, the new energy and environmental measures will not meet with unanimous approval.

Firstly, many believe that Colombia’s efforts are disproportionate to the country’s real impact on global climate change. Sergio Guzman, director of the Colombia Risk Analysis institute, points out that “it’s not up to a country like Colombia, with its very poor infrastructure, to assume the cost of the energy transition”, even though the country produces “only” 0.3% of the world’s CO2 emissions.

In addition, a large part of the hydrocarbon industry is concerned about the potential impact of this rapid energy transition on the country’s economy. Indeed, many voices from the fossil fuel industry are raising the issue of reducing the amount of foreign investment in the country, due to the diminishing profitability of hydrocarbon projects. These concerns were well-founded, since by the end of 2022, the year of Petro’s election, investors, worried about rising taxes on gas, oil and coal, were dumping government bonds. This situation will cause the peso to fall from the end of 2022.

Finally, the energy transition is also a source of controversy among indigenous populations. In the northern department of La Guajira, home to the Wayuu, Colombia’s largest indigenous community, opposition to wind farm projects is strong. And yet, the La Guajira desert is considered to be the best site for wind power in South America in terms of electricity production potential. While the desert, which makes up around 1% of Colombia’s total surface area, could supply eighteen gigawatts of electricity, the rest of the country provides thirty gigawatts. However, wind power projects in the region are often perceived as following a similar dynamic to traditional extractivism, the benefits of which indigenous communities do not see. This is despite the “Pact for a Just Transition” initiated by Gustavo Petro, which aims to distribute the benefits of wind-generated electricity production at local level.

Thus, for Joanna Barney, director at the Indepaz Institute, “anything you do in La Guajira – if you don’t have the social sensitivity that comes from having visited the territory and knowing it – is detrimental”. For Irene Vélez Torres, former Petro minister, the government’s energy transition “has its challenges”. However, using the example of the “Pact for a Just Transition”, she believes that the current energy policy under Petro remains “the way forward in this government […] and in those to follow”.

Thus, for Joanna Barney, director at the Indepaz Institute, “anything you do in La Guajira – if you don’t have the social sensitivity that comes from having visited the territory and knowing it – is detrimental”. For Irene Vélez Torres, former Petro minister, the government’s energy transition “has its challenges”. However, using the example of the “Pact for a Just Transition”, she believes that the current energy policy under Petro remains “the way forward in this government […] and in those to follow”.

Future prospects and challenges

In view of the measures outlined above, and despite the ensuing challenges, the outlook for the energy transition under Petro can be considered optimistic. For Swedish activist and researcher Andreas Malm, the end of the oil industry in Colombia should be reached in the medium term. Speaking at a conference organized by the Institut La Boétie geography chair in Paris on March 30, the author declared that “perhaps if (Gustavo Petro’s policy) continues, in 10 years’ time the oil industry in Colombia will cease to exist”. Indeed, Malm pointed out on this occasion that if reserves are exploited and exploration ceases, the Colombian oil industry should come to an end in the next few years. Meanwhile, at regional level, Petro’s slogan of “debt for life” is slowly making inroads in the South, even if it hasn’t yet received the support of any debtor country or financial institution.

However, the road to a successful energy transition in Colombia remains fraught with difficulties. In addition to the aforementioned obstacles, the constraints Petro inherited from his predecessor – peso depreciation, high debt and slow growth – have been reinforced under his presidency. What’s more, according to figures put forward by the Invamer polling institute, the President’s disapproval rating has now risen to 60%, with a loss of support from political forces both within Congress and in public opinion. On Sunday April 21, nearly 500,000 people took part in demonstrations against the Petro government, according to the combined figures released by the mayors of Cali Bogotá, Barranquilla, Cartagena and Medellin, the country’s second largest city. At issue is Petro’s healthcare reform, which has drawn fierce criticism from dozens of doctors’ associations and a significant proportion of the population.

So, with only two years to go before the next presidential elections in Colombia, the timeframe is shrinking for Gustavo Petro. The author of ambitious reforms, some of which are unique on the American continent, Gustavo Petro wants to make Colombia an example of how to move away from hydrocarbons, and a leader in energy transition on a global scale. However, the country’s dependence on hydrocarbons weighs heavily on industry’s and the population’s acceptance of these reforms, given Colombia’s low overall impact in terms of greenhouse gas emissions. It’s probably too early to judge the effectiveness of the reforms implemented by the Petro government, but they undoubtedly embody a long-term dynamic for Colombia that could outlast its president.

Indeed, although Petro today represents a form of exception, in terms of the style and “radicalness” of the measures taken, his climate policy could well herald the transformations to come for his successors. Already, at COP28, we can see the emergence of a new deal for hydrocarbons. After nearly three decades during which negotiators failed to include fossil fuels in climate agreements, a global consensus is now emerging to advocate their gradual reduction. Petro embodies part of this upheaval. However, it is certain that the pressing urgency of climate change will engender a growing number of leaders, in Colombia and elsewhere, ready to tackle climate and environmental challenges from innovative angles. Even if this means sacrificing sectors that are economically profitable in the short term, in favor of a genuine “policy for life”.