According to BloombergNEF, global carbon emissions from the energy sector should fall by 10% by 2020. Wind and solar power will provide 56% of the world’s electricity by 2050.

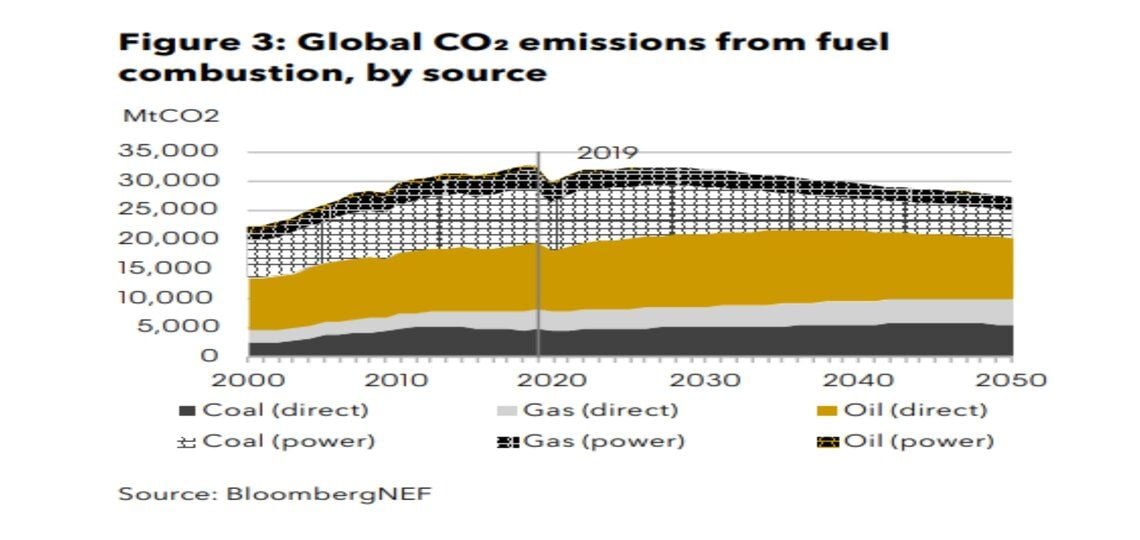

Carbon emissions to decline year-on-year after 2027

According to projections by BloombergNEF (BNEF), the global drop in energy demand caused by the coronavirus will reduce sector-wide emissions by 10% this year and eliminate 2.5 years of global emissions by 2050.

Earlier this year, the International Energy Agency (IEA) revealed that global carbon emissions stabilized in 2019. This announcement follows two consecutive years of growth, to around 33 gigatons.

While economic recovery from the pandemic will see energy-related emissions rise by 2027, they will not return to the level reached in 2019. And from 2027 onwards, there will be an annual drop of 0.7% until mid-century.

However, this won’t even come close to the 1.5 degree Celsius limit for global warming. This was the objective of the Paris Agreement on climate change. BNEF’s research estimates that the rate of reduction in carbon emissions from the energy sector needed to meet this target is 10% each year between now and 2050.

Wind and solar power are key to reducing carbon emissions from the energy sector

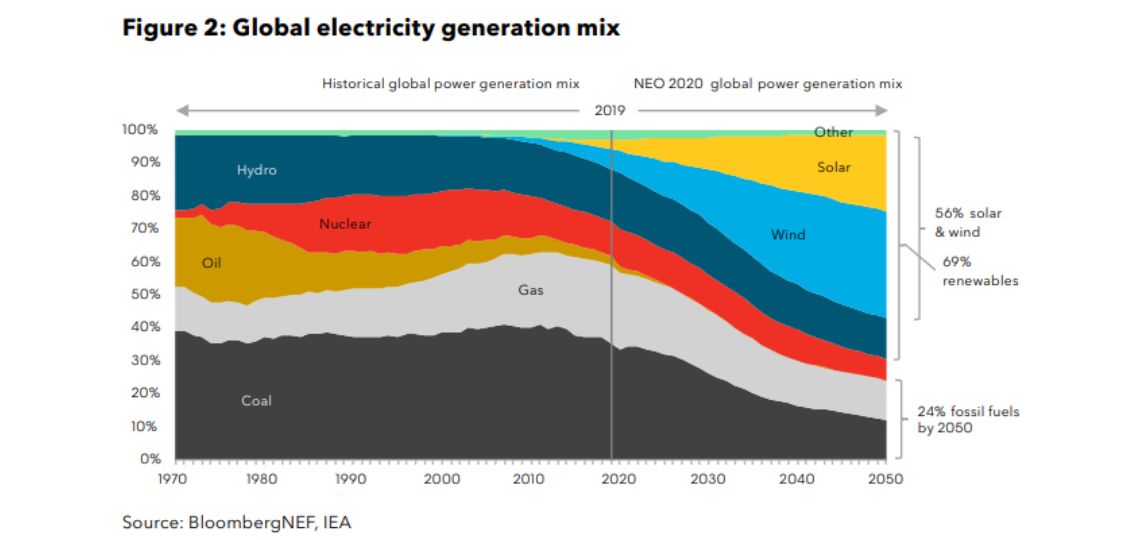

Increasingly competitive wind and solar power will stimulate the ongoing decarbonization of energy consumption. The accelerated adoption of electric vehicles and advances in energy efficiency across all industries will also be important.

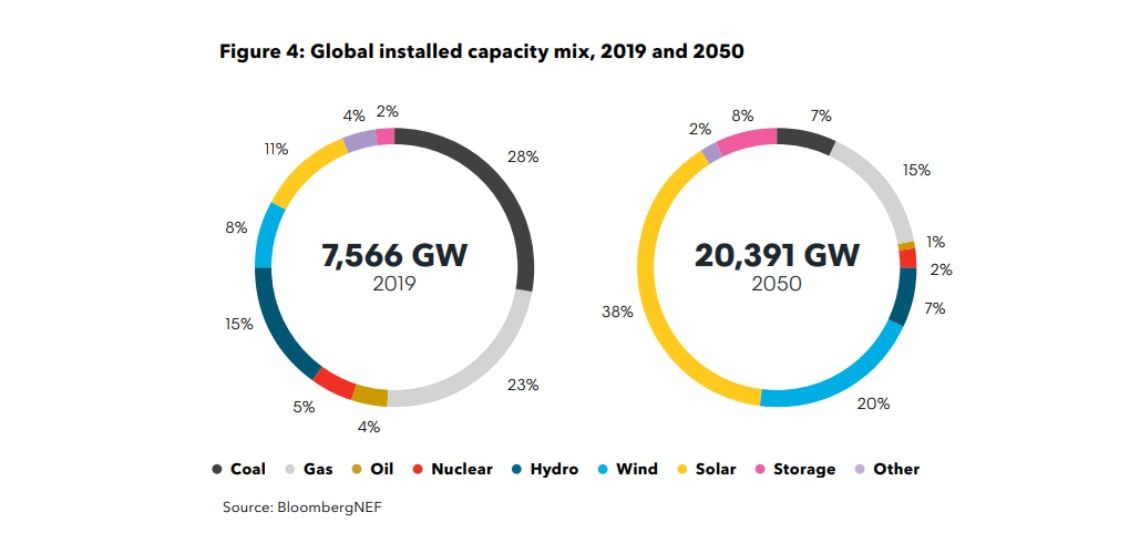

It is estimated that 13 billion euros will be invested in new capacity over the next three decades. Wind power, solar power and batteries are expected to account for 80%. Just under half of all new capital will be injected in the Asia-Pacific region.

Fueled by this investment, wind and solar power should account for 58% of the world’s electricity production by 2050. According to current estimates, these energy sources currently account for 10% of the global electricity market.

A further 11 billion euros will have to be invested in modernizing and expanding electricity networks. This is to take account of the growing electrification of energy systems and the ensuing changes in supply and demand.

“The next ten years will be crucial for the energy transition,” said Jon Moore, CEO of BNEF. “There are three key elements we will need to see: accelerated deployment of wind power and photovoltaics; faster adoption of electric vehicles, small-scale renewables and low-carbon heating technologies such as heat pumps; and large-scale development and deployment.”

The outlook for fossil fuels

Natural gas will be the only fossil fuel not to experience a peak in demand before 2050. It is expected to grow at an annual rate of 0.5% over the period. Buildings and industry will account for 33% and 23% of its growth respectively, as sectors where there are “few low-carbon economic substitutes”.

BNEF’s New Energy Outlook 2020 predicts that coal-fired power generation in China will peak in 2027. China is by far the world’s biggest coal consumer. However, the country is committed to achieving net zero emissions by 2060.

In India, where coal is still an important part of the national energy mix, fossil fuel-fired power generation is set to reach its peak in 2030.

Overall, coal is expected to account for 12% of the world’s electricity supply by 2050, compared with around 33% today.

BNEF’s analysis suggests that oil demand will peak in 2035. This is later than some forecasts, including those of BP and the IEA.

Scaling up green hydrogen to reduce carbon emissions

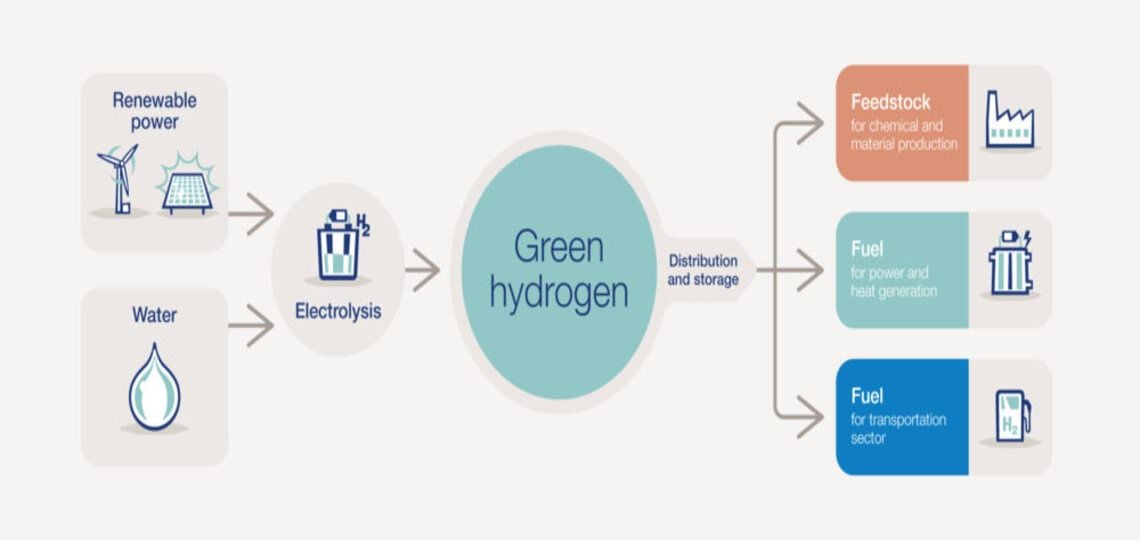

Hydrogen fuel – particularly “green” hydrogen – has been widely tipped to emerge as a low-carbon alternative energy carrier. But for it to have a significant impact, there are several cost and scale challenges to overcome.

Under BNEF’s “climate scenario” – which forecasts ways to keep global warming well below two degrees Celsius by 2050 – around 100,000 terawatt-hours (TWh) of global electricity generation will be needed by 2050 to meet growing demand.

“This power grid is six to eight times larger than today’s. It has twice the peak demand and produces five times as much electricity,” according to the report. “Two-thirds of this electricity is used for the direct supply of electricity in transport, industry, etc. The rest is used to manufacture green hydrogen.

In the scenario, green hydrogen supplies just under a quarter of final energy consumption by mid-century.

This would require 800 million tonnes of fuel and 36,000 TWh of electricity. In other words 38% more than is produced in the world today. What’s more, this will require up to $130 billion in new investment over the next 30 years.

This would represent around 60 billion euros spent on electricity generation and the electricity grid for direct electricity supply. But also between 11 and 63 billion euros devoted to the manufacture, transport and storage of hydrogen.