At the end of a windswept pier on the North Sea lies Germany’s most strategic construction site: the building of the country’s first liquefied gas terminal.

Located near the port of Wilhelmshaven on the North Sea coast, this platform will be able to supply, as of this winter, the equivalent of 20% of what Russian gas imports to Germany represented until recently.

They were stopped in the wake of the war in Ukraine.

A total of five projects have been launched this year by the government at great expense to compensate for the end of Gazprom deliveries.

From 2023 onwards, the project will deliver 25 billion cubic meters per year, half the capacity of the Nord Stream pipeline.

– Trucks –

On the construction site in Wilhelmshaven, workers dressed in fluorescent yellow are working in the drizzle on the surface of a half-finished concrete platform that is emerging from the water.

On land, a ballet of trucks brings pieces of grey pipe to the construction site, transported by cranes, before being linked together to connect the terminal to the existing 28-kilometer network.

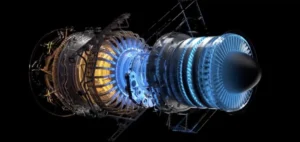

LNG terminals allow the regasification of natural gas imported by sea, which has first been liquefied to make it more transportable.

They consist of an offshore platform connected by pipes to the onshore gas network.

A boat called FSRU is moored there, rented for several years.

It stores and regasifies liquid gas.

Unlike other European countries, Germany had no such equipment either onshore or offshore, preferring to benefit from the cheap resource from Russian pipelines.

But after the invasion of Ukraine, Russia first significantly reduced its deliveries, which previously accounted for 55% of German imports, before stopping them in early September.

To ensure its energy security and save its gas-intensive industry, Berlin is investing heavily in LNG.

The government has already signed agreements with Gulf countries such as the United Arab Emirates and Qatar to import more liquefied gas.

Berlin has also released three billion euros to lease FSRU vessels to equip its terminals.

– Environment –

The country passed a law in the spring that significantly accelerated the procedures for opening terminals quickly.

In Wilhelmshaven, the construction work is progressing rapidly. These networks can be seen installed in the middle of fields or pastures where dairy cows are still grazing.

The terminal should therefore be completed “as early as this winter,” Holger Kreetz, chief operating officer of the German energy group Uniper, which manages the project, told AFP.

This unusual speed is a sign that the government considers this subject a priority: “Normally, we complete a project like this in 5 or 6 years,” adds Mr. Kreetz.

The initiative is generally well received in a city marked by deindustrialization and where the unemployment rate exceeds 10%, which is almost twice the national average.

“It’s good that it’s in Wilhelmshaven (…) It will bring back jobs,” Ingrid Schon, 55, told AFP, as she passed by on the town’s main street.

On the contrary, some environmental associations denounce the risks associated with the acceleration of environmental impact assessment procedures.

Young activists of the German movement “Ende Gelände” blocked the construction of the Wilhelmshaven for one day in August.

For the DUH association, the project “irreversibly destroys sensitive ecosystems and will endanger the living space of porpoises”.

The origin of the imported gas, which could be the result of hydraulic fracturing in the United States, a practice that is environmentally controversial, is also being questioned.

These criticisms have been brushed aside by Climate Minister Robert Habeck, who is nevertheless an environmentalist, and who insists that the government’s priority is “energy security”.

By 2030, the site is to be converted to green hydrogen, a clean technology in which Berlin wants to become the champion in the coming decades.